|

‘While Shepherds Watched their Flocks by Night:’ |

|

|

Prof.

Em. Ian Russell, MBE, Elphinstone Institute,

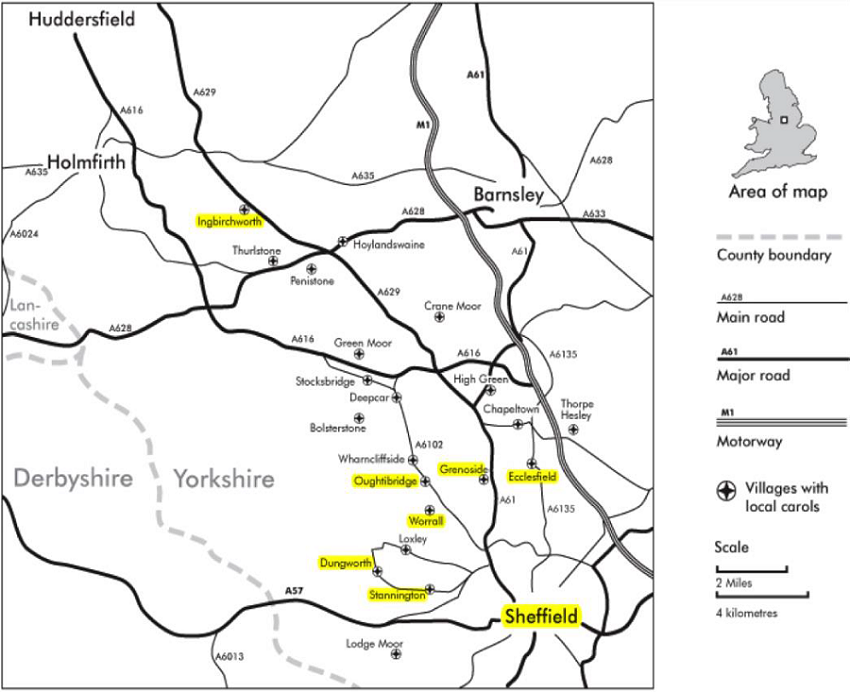

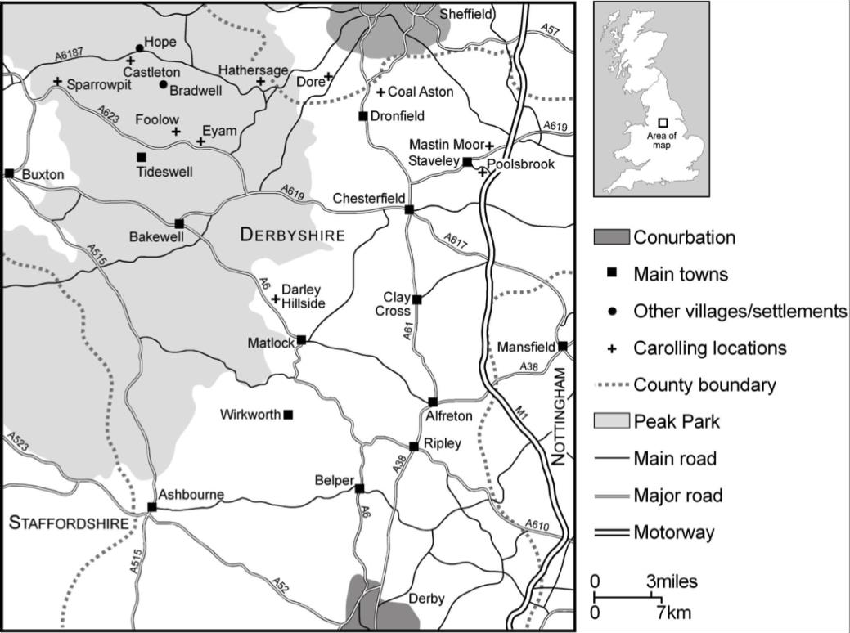

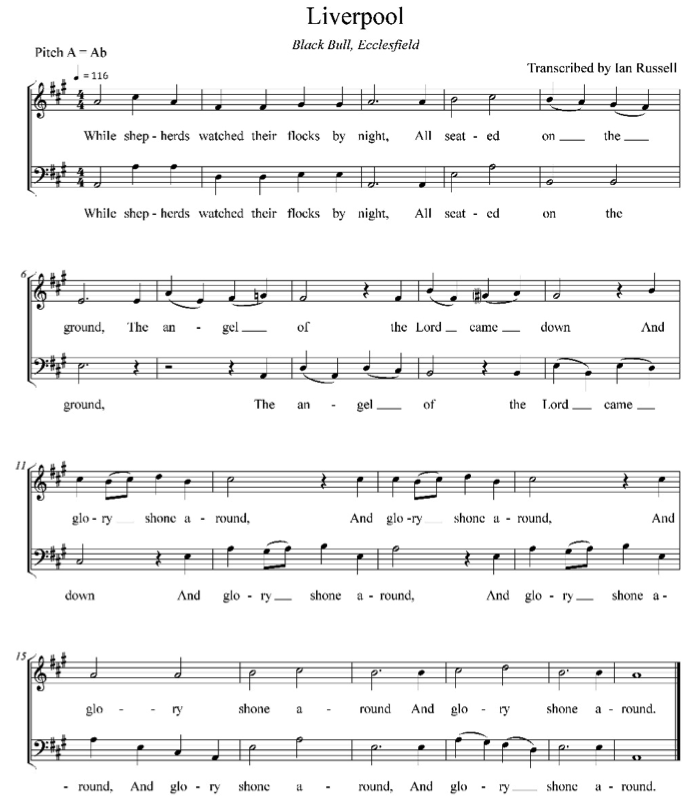

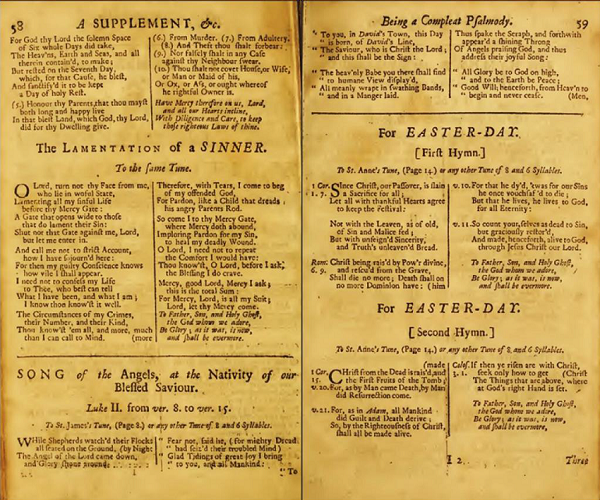

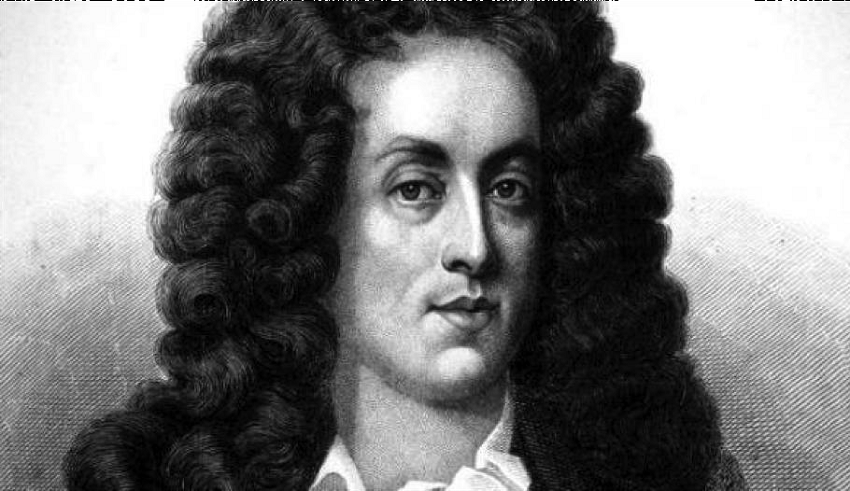

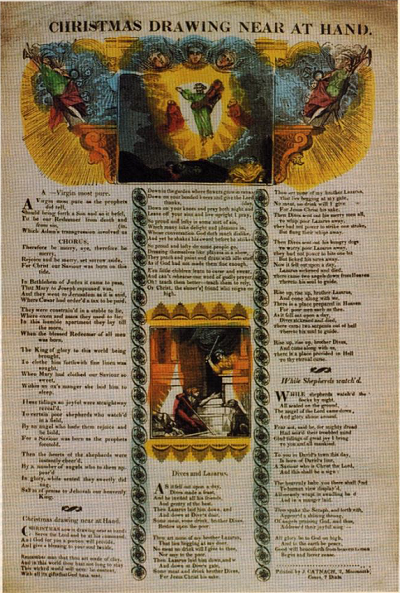

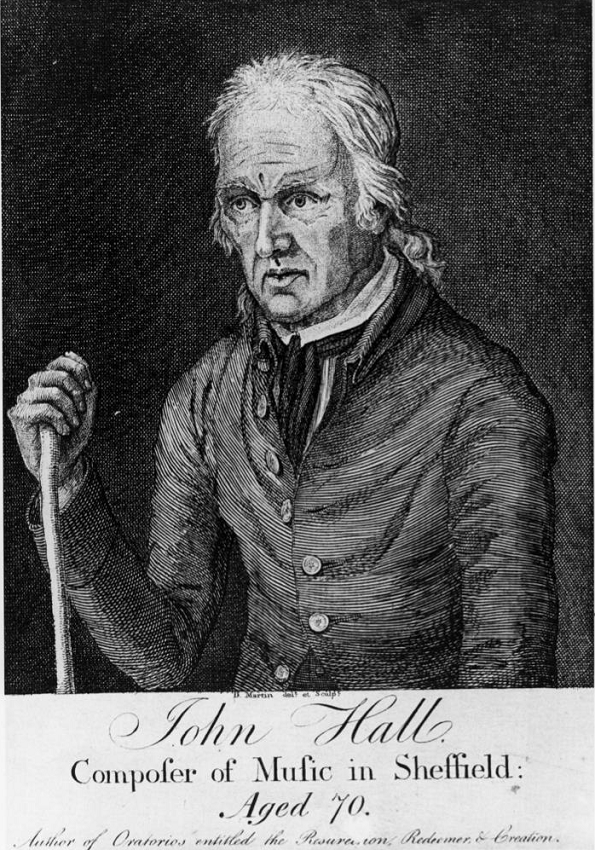

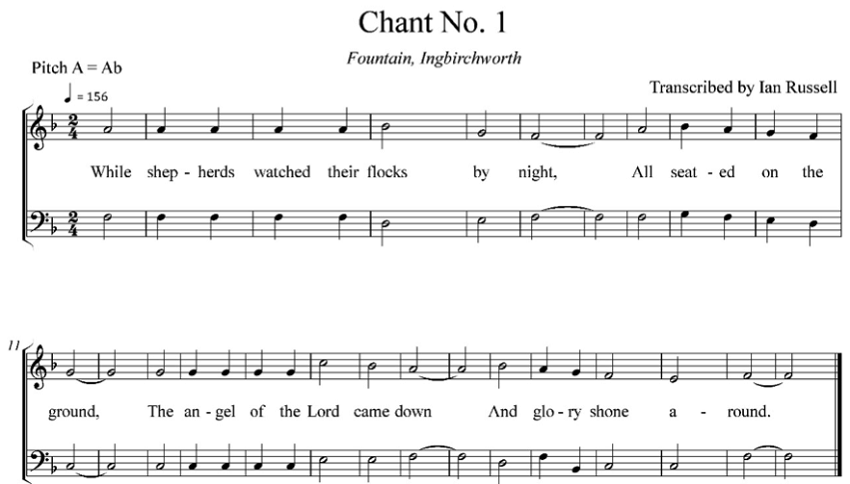

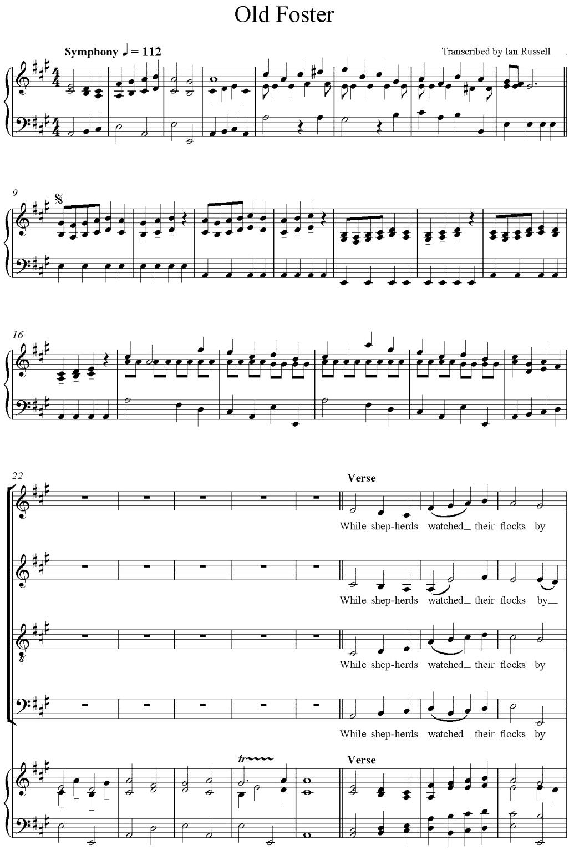

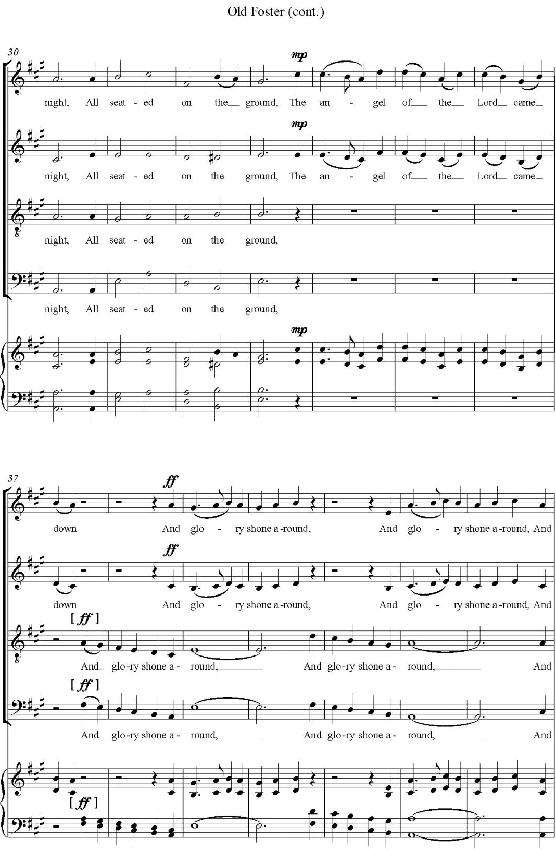

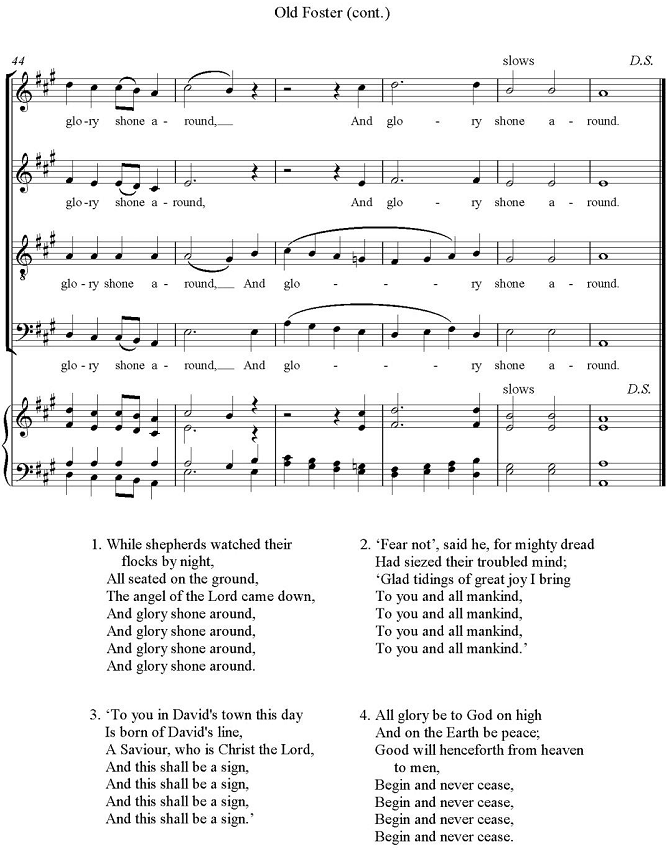

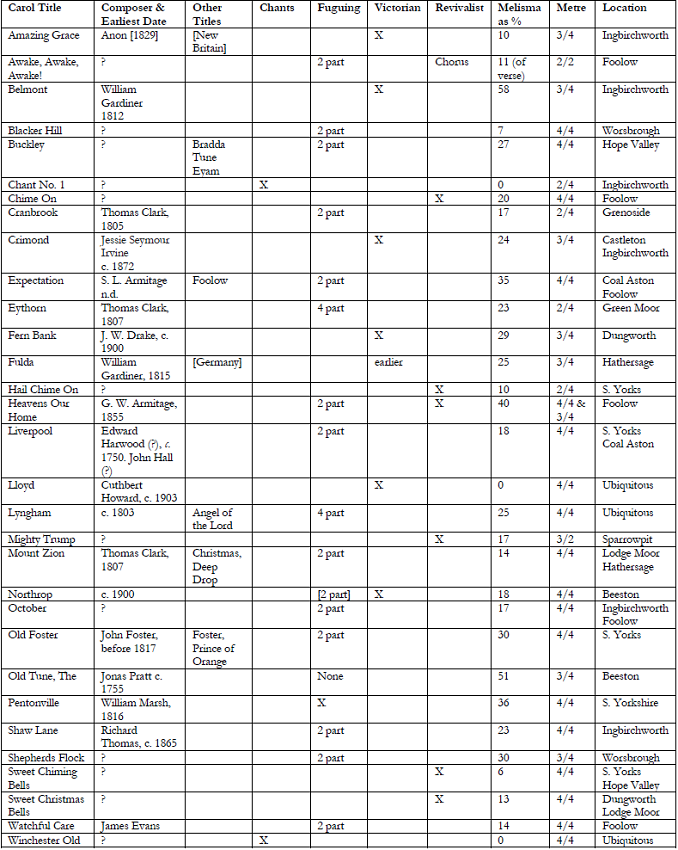

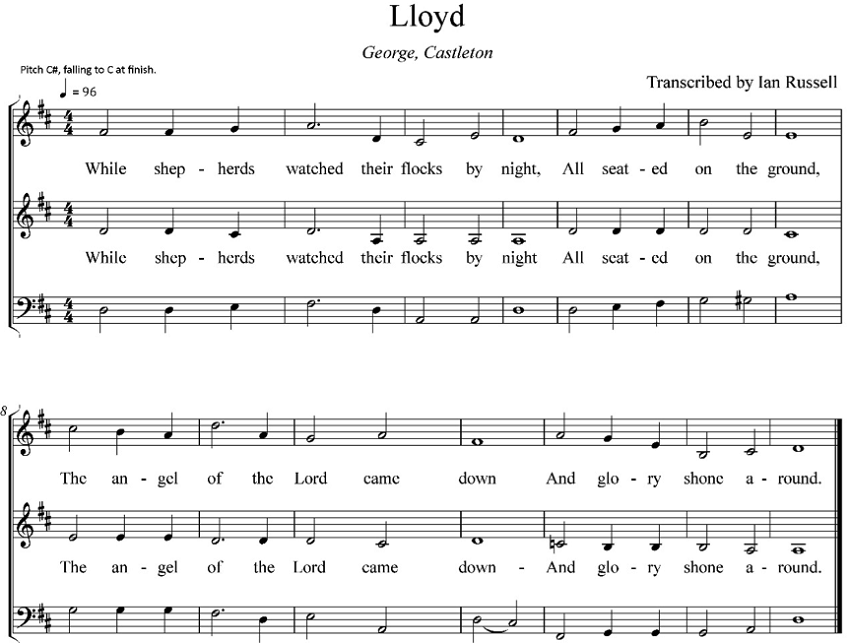

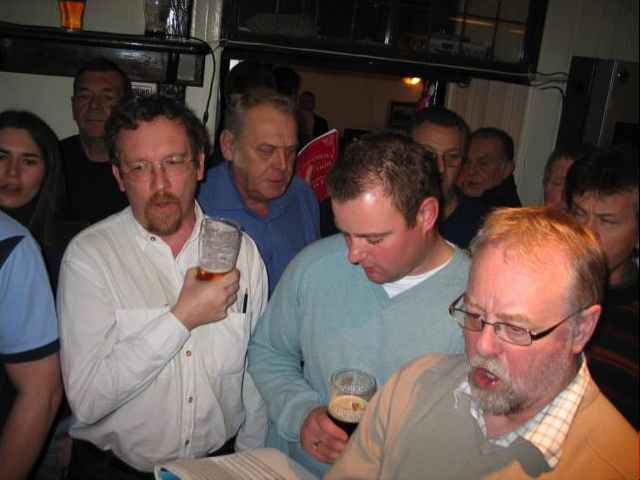

University of Aberdeen (UK) published 4th April 2022 In the vernacular tradition of English village carolling, as it is performed in the southern Pennine hills, one text occurs in more musical settings than all others. This is the carol ‘While Shepherds Watched their Flocks by Night’ (hereafter ‘While Shepherds Watched’). Since 1969 I have recorded in oral tradition more than 30 different tunes to which these words are sung within 40 kilometres of the city of Sheffield (see Fig. 1 and 2)2. That number could easily be doubled if I took into account the tunes found in manuscripts and locally circulated printed collections assigned to this text.  Figure 1 Carolling Villages to the North of Sheffield.  Figure 2 Carolling Villages to the South of Sheffield. In

this article I aim to explain the unrivalled

popularity of this carol in terms of its intrinsic

qualities, its musical expression and performance,

and its historical development. One of the most

popular tunes is ‘Liverpool,’3 a

transcription of which is shown in Fig.

3 together with photographs of the

carollers (see Fig.

4a and 4b),

and an audio example from the Black Bull in

Ecclesfield is available  Figure 3 ‘Liverpool’, as sung at the Black Bull, Ecclesfield, 5 December 2013.  Figure 4a Carollers at the Black Bull in Ecclesfield, 8 December 2011. Photograph: Ian Russell  Figure 4b Carollers at the Black Bull in Ecclesfield, 15 December 2011. Photograph: Ian Russell. I have chosen the term ‘paradigm’ for very conscious reasons. Firstly because the chosen carol is a model of its genre, or a very clear and typical example of it (Oxford English Dictionary 1986), but also because at a deeper level this research embodies the importance of an approach that combines ethnographic fieldwork of the vernacular tradition of carol singing with grounded historical research based on documentary evidence. My aim is to demonstrate, as Lomax (1968, 298) has noted, how such a paradigm as a carol can characterise a culture in terms of its basic structural elements (text and tune), and its wider complexity, including its role in social interaction, its transmission through oral tradition and print, its resonances and purposes, and an understanding of the enactment milieux, including style and aesthetics (Stone 2008, 3–11). Like most musical traditions, the carolling tradition of the English Pennines presents the researcher with a palimpsest of complex data from which to draw a narrative that gives an insight into their context, meaning, function, and performance. To the participant in the tradition such an analytical approach is somewhat alien. They see the tradition as a whole, the components of the repertoire as constituent parts of a unitary body, its expression as consistent, its performance context as rooted, and its evolution as timeless. The contrasting perspectives of the insider/performer and the outsider/researcher have been encapsulated in two terms ‘etic’ and ‘emic’ coined by the linguist Kenneth Pike (1967). The text The text of the carol has been dated to 1700 when it was first published in A Supplement to A New Version of the Psalms of David, edited by N. [Nicholas] Brady and N. [Nahum] Tate, under the title ‘Song of the Angels, at the Nativity of our Blessed Saviour.’4 Taken from the Gospel of Luke II: 8–15, it is a metrical version in quatrains, known as common metre or ballad metre (see Fig. 5 and below). The paraphrase is attributed to one of the editors, Nahum Tate (1652–1715), an Irishman who was appointed Poet Laureate in 1692 (see Fig. 6). He is noted for his rewrite of Shakespeare’s King Lear (1681), complete with happy ending, which became the dominant version of the play for over a century and a half.  Figure 5 ‘Song of the Angels, at the Nativity of our Blessed Saviour’: ‘While Shepherds watch’d their Flocks by Night’ from Brady – Tate 1700, 58–59. Text attributed to Nahum Tate.  Figure 6 Nahum Tate, 1652–1715, Poet Laureate of England, anonymous engraving, London c.1685. Public domain. ‘While Shepherds Watched’ is a very effective piece of verse, remarkable in its simplicity and for its use of vernacular language, such that it has never been significantly rewritten or updated (Gant 2014, 109 and 112–13). The final triumphant verse written in plain English is taken from Luke’s gospel, II: 13–14, having previously been known in Latin as, ‘Gloria in Excelsis Deo.’ It was in fact the first hymn or carol celebrating Christmas to be sanctioned for use in the established church (the Church of England), since the time of the Puritans, who some fifty years earlier had not only abolished the celebration of the feast of Christmas but banned the singing of Christmas carols5. Undoubtedly the carol had widespread appeal, contrasting the pastoral upland setting of the shepherds keeping watch over their sheep with the dramatic and sudden apparition of the angelic host. It continued to occupy a privileged status for over 80 years until two further texts were added to the official list, one of which was Charles Wesley’s ‘Hark! the Herald Angels Sing’ (Keyte and Parrott 1992, 328). Fortunately, such sanctions of the established church were not universally recognised in England, especially by Nonconformist congregations, and the practice of singing carols outside of church was largely unaffected6. The popularity of this carol text was not entirely due to its privileged status within the established church. The carol was also printed on many broadsides, such as the sheet from James Catnach of 7 Dials in London, which were widely distributed by chapmen and pedlars (see Fig. 7). The copy has been hand- coloured so that the seller could charge a higher price – the saying was “penny plain, tuppence coloured7”. This ensured that copies of the carol were readily available in the home and at the inn (the village pub), and not just within the confines of the church.  Figure 7 ‘Christmas Drawing Near at Hand’, early nineteenth-century carol broadside, hand coloured. By J. Catnach of 7 Dials, London, c. 1825. Firth Collection, Sheffield University Library. Musical Developments Although the recommended tune in the Supplement, ‘St. James’s’ by Raphael Courteville, was never taken up by congregations, the verse structure of the carol rendered it suitable for use with innumerable settings/tunes over the next three centuries: this structure has 4.3.4.3 stresses, known in poetry as ballad metre (four lines of alternating iambic tetrameter and iambic trimeter), and 8.6.8.6 syllables, known in hymnody as common metre/measure or CM. In the early 1700s there was a shortage of music suitable for congregational singing in English parish churches. The available repertoire typically included plainchants or simple melodies which were “lined out”8 by a precentor (the parish clerk or the priest), responded to by the congregation, and were performed slowly, in heterophony9. This dearth of music-making was transformed into an abundance by the mid-1700s as a result of the creativity of local village musicians, most of whom were skilled craftsmen from the artisan class, often lacking in formal musical training, who wrote for their local communities or church congregations. One such, John Hall of Sheffield Park, a blacksmith, who died in 1794, composed the tunes for several carols which were absorbed into the local tradition (see Fig. 8). Their compositions, for the singing of psalms, hymns, anthems, oratorios, as well as carols, were characterised by exuberant delivery, repetition of lines of text, instrumental virtuosity, and the use of melisma and fuguing passages, influenced by the music of the Baroque, notably Bach and Handel. A special place in the form of a raised gallery within the west end of parish churches was created for the singers and instrumentalists from which to perform (see Fig. 9). The heyday for this style of music in the Sheffield region was approximately 1760–1820.  Figure 8 John Hall, Blacksmith of Sheffield Park, d. 1794. Sheffield City Libraries. ![‘A Village Choir’ [in 1820], oil painting by Thomas Webster (1800–1886). Victoria & Albert Museum, FA.222[O].](664172061006_gf11.png) Figure 9 ‘A Village Choir’ [in 1820], oil painting by Thomas Webster (1800–1886). Victoria & Albert Museum, FA.222[O]. By the late 1820s, however, the ‘quires,’ who performed this type of music with great energy and flamboyance, attracted the disapproval of High Church reformers, namely the groups who are referred to as the Tractarians and the Oxford Movement.10 They saw the music as undermining the authority of the church. Their reforms, which in the first half of the nineteenth century affected all aspects of church worship from the liturgy to church interior design, saw the performance of ‘Georgian psalmody,’ as it is sometimes labelled, outlawed and its performers exiled. By the time of the publication of Hymns Ancient and Modern in 1861 (Monk 1861), England’s first mass-produced hymnbook, the reform was virtually complete with surpliced choirboys taking the place of the redundant ‘quires,’ and newly installed church organs replacing the sacked bands of instrumentalists (see Gammon 1981, 72–80; Temperley 1979, 151– 63). Many of the supporters simply took their music with them into the newly-formed Nonconformist churches, where it was initially welcomed (but not for long), or literally out on the streets where the music was reserved for use at Christmastide and absorbed into existing perambulatory house-visiting customs as locally distinct traditions. Here, the carols were outside church jurisdiction and thrived on it. By the end of the nineteenth century the local traditions had become further secularised by the introduction of carol singing into the pubs, especially in the South Pennines of Yorkshire and Derbyshire (Russell 2017, 68–82). In the Oral Tradition In virtually every community that nurtured a repertoire of ‘local’ carols at least one of them was, and in many cases still is, a setting of ‘While Shepherds Watched.’ For example, at Foolow in the Derbyshire Peak District and Ingbirchworth in South Yorkshire seven different settings have been recorded at each location (see Fig. 10).  Figure 10 Foolow Carollers, Christmas Day 1957. Photograph: Tony Davis. The table in the Appendix 2 lists the 31 tunes that I have recorded from oral tradition, their provenance, musical genre, and essential characteristics. The oldest and smallest group of tunes are the chants used for the singing of metrical psalms. There are just two in number and one of these, ‘Winchester Old,’ is the standard tune used in churches in the UK today. In fact, there is no evidence to suggest that the words and this tune were combined before 1861, when the editors of Hymns Ancient and Modern set ‘While Shepherds Watched’ to ‘Winchester Old’ (no. 62).11 As part of the policy to displace the eighteenth-century melismatic tunes from the official record, the editors deliberately sought out sixteenth-century chants for their ‘purity’ and sublimity. In their original conception such chants were monodic, plain and unadorned. The example given here is ‘Chant No. 1,’ as sung in Ingbirchworth and the Penistone district; the writer of the tune is not known (see Fig. 11).  Figure 11 ‘Chant no. 1’ as sung at the Fountain Inn, Ingbirchworth, 14 December 1986. Our next group chronologically comprises the fuguing and melismatic tunes, fourteen of them, representing the largest and most popular group. The dates of their composition vary by more than a century – one or two predate 1760, most of them are from the 1760–1830 period whereas there is one from as late as c. 1900 (Northrop), which has elements of fuguing. As part of their polyphonic nature, these tunes demonstrate fuguing in two, three or four parts expressed through imitative entries, which create textual overlaps. Unusually ‘The Old Tune’ recorded in Beeston, which dates from the mid- eighteenth century, has a high incidence of melisma but no fuguing. Another tune, ‘Awake, Awake, Awake!’ from Foolow bears all the hallmarks of an eighteenth-century fuguing tune but the chorus is late nineteenth century ‘revivalist’ in character. ‘Old Foster,’ which was written before 1817 by John Foster of High Green (1752–1822), encapsulates this form in all its splendour including an instrumental interlude between the verses known as the ‘symphony’ (see Fig. 12, Appendix 1).12 [Audio Example 2: ‘Old Foster,’ Blue Ball, Worrall, 12 December 2004] Next page: Appendix 1 (Figure 12)  Figure 12 ‘Old Foster’ as sung at the Blue Ball, Worrall, 12 December 2004.  Figure 12 (continuation) ‘Old Foster’ as sung at the Blue Ball, Worrall, 12 December 2004.  Figure 12 (continuation) ‘Old Foster’ as sung at the Blue Ball, Worrall, 12 December 2004.  Appendix 2 Tunes for ‘While Shepherds Watched’ Recorded from Oral Tradition The third group comprises settings that are broadly Victorian in origin. Most are universally popular tunes, quite apart from their use for ‘While Shepherds Watched’ and include ‘Crimond’, ‘Belmont’, ‘Amazing Grace’, and ‘Lloyd’ (see Fig. 13 and 14).13 [Audio Example 3: ‘Lloyd,’ George, Castleton, 14 December 2008].  Figure 13 Carolling at the Cheshire Cheese, Castleton, 19 December 2004. Photograph: Derek Schofield.  Figure 14 ‘Lloyd,’ as sung at the George, Castleton, 14 December 2008. These conventional, four-square tunes feature pleasing harmonic progressions with a strong emotional appeal to singers and audiences. Although they are characterised by one note per syllable supported by a simple chord and engaging harmonic progressions, both ‘Crimond’ and ‘Amazing Grace’ contain examples of passing notes and anticipatory intervals while ‘Belmont’ is rife with these features. Our fourth and final group includes evangelical ‘revivalist’ tunes popular in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, especially among Salvationist congregations.14 They are mostly very lively with simple memorable melodies, such as ‘Sweet Chiming Bells,’ and take the form of verse and chorus. An American influence from Moody and Sankey is in evidence15 and in some tunes there are dotted rhythms and syncopation (see Fig. 15).16 [Audio Example 4: ‘Sweet Chiming Bells,’ Travellers Rest, Oughtibridge, 5 December 1992].  Figure 15 Carolling at the Traveller’s Rest in Oughtibridge, 8 December 2007. Photograph: Ian Russell. Photograph: Ian Russell. It is interesting to note that almost a third of the tunes are in triple time/metre. Concerning Repertoire and Repetition At midday on the first Sunday after the 11 November (Armistice Day or Remembrance Sunday – whichever is the latest), the Christmas carol singing season starts in the Blue Ball Inn in Worrall, one of several singing pubs in communities to the north and north-west of Sheffield. People arrive in good time, some as much as an hour before the start and crowd into the singing room, a modest venue which at other times is reserved for the playing of pool (bar billiards). Drinks are ordered through a hatchway and the room is heavy with conversation between carollers, exchanging news and sharing stories. Male voices dominate the session by two to one such that, as the introduction to the first carol is completed by the organist, Julia Bishop, the unsuspecting newcomer is hit by a wall of sound (see Fig. 16a and 16b). There are times during the two-hour session when the room seems to vibrate as if it is overwhelmed by the volume and cannot hold any more. An atmosphere of excitement is generated among the carollers such that a momentum is built by the sheer density of voices. The transformative nature of this exuberant singing creates what Edward Hall has described as “social synchrony,”17 which, in turn, leads to a state of ‘flow’ – a term used by Csikzsentmihalyi (1988).  Figure 16a Carolling at the Blue Ball, Worrall, organist Julia Bishop, 9 December 2007.  16b Carolling at the Blue Ball, Worrall, organist Julia Bishop, 9 December 2007. Photographs: Ian Russell. Undoubtedly to achieve ‘flow’ demands a high level of familiarity with the repertoire – no mean feat, as more than twenty different carols may be performed in a single session. Amongst these there will almost certainly be three or four settings of ‘While Shepherds Watched.’ In repeating the text for each of these, the performers receive a form of respite – without the need to recall several different texts they can feel confident in their memorisation of the words and focus on the enjoyment of the tune and its performance, reaching a climax in the final verse, “All glory be to God on High ... Begin and never cease.” There are other texts that may also be repeated to a lesser extent – notably ‘Hark, Hark! What News’ – which offers the same benefit.18 In an atmosphere of bravado, impromptu carolling sessions have been known to feature nothing but settings of ‘While Shepherds Watched,’ an accolade being reserved for the singer who can keep coming up with different tunes for the text. Similarly I have conducted workshops at festivals devoted to ‘While Shepherds Watched’ with equal success.19 The fact that the words are constantly being repeated to distinctive melodies, adds to, rather than detracts from, the buzz, providing ease of performance as well as transgressive humour and a sense of mischief-making. In such situations the significance of the words shifts from a semantic to a ritualistic or symbolic function. The inner meaning of the narrative is no longer what matters to the singers, rather the text provides the appropriate vehicle to enable performance of the many associated melodies and their fulfilment as distinct acts of carolling. Conclusion The phenomenon of the overwhelming popularity of the carol text ‘While Shepherds Watched’ over three centuries is not due to its intrinsic qualities as a work of poetical genius or spiritual merit. Rather it is the simplicity of language, the familiar balladic structure, and the unpretentious narrative, which stays true to Luke’s Gospel, which has provided an enduring means to an end, that is to enable the enjoyment of singing carols as a vernacular expression of the seasonal celebration of Christmas by reiterating the symbolic narrative. This expression has not been prescribed or controlled by the arbiters of musical taste or doctrinal belief, through the influence of the church hierarchy or the mass media, but represents a dynamic grassroots movement in which individuals and individual communities have created and recreated oral traditions over the generations built on the musical and material resources available to them. In essence ‘While Shepherds Watched’ is the people’s choice, not for its singularity but its plurality, its utility, its adaptability, and the understated universality of its appeal. By way of a postscript here is a further example of the carol from the diaspora of the South Pennines, as it is sung in the community of Glen Rock, York County, Pennsylvania, USA, whose forebears emigrated in the 1840s from the Cheshire-Derbyshire border to start a new life (Glatfelter 2007). To exploit the natural resources of water-power and local agricultural abundance of sheep production, they built a woollen mill. The tune for ‘While Shepherds Watched’ that they took with them is sung in oral tradition in Derbyshire, in Foolow and Castleton, where it is known as ‘Once More’ (see Fig. 17).20 [Audio Example 5: ‘While Shepherds’ Glen Rock Carolers, 24 December 1997].  Figure 17 Glen Rock Carolers from York County, Pennsylvania, on their visit to Sheffield, 2 December 2012. Photograph: Ian Russell. References 1 Csikszentmihalyi Mihal, and Isabella S. Csikszentmihalyi, eds. 1988. Optimal Experience: Psychological Studies of Flow in Consciousness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2 Foster, John. c. 1817. Sacred Music, 2 vols. York: n.d. 3 Gammon, Vic. 1981. “Babylonian Performances: The Rise and Suppression of Popular Church Music, 1670–1860.” in Popular Culture and Class Conflict, edited by Eileen Yeo and Stephen Yeo, 62–88. Brighton: Harvester Press. 4 Gant, Andrew. 2014. Christmas Carols: From Village Green to Church Choir. London: Profile Books. 5 Glatfelter, Charles H. 2007. Salute this Happy Morn: A History of the Glen Rock Carol Singers. revd edn. Glen Rock PA: Glen Rock Carolers Association. 6 Hone, William. 1823. Ancient Mysteries Described. London: William Hone 7 Glen Rock Carolers. 1997. Voices of Christmas, CD. Glen Rock PA. Hone, William. 1823. Ancient Mysteries Described. London: William Hone.

8 Keyte, Hugh, and Andrew Parrott, eds. 1992. The

New Oxford Book of Carols. Oxford and New York:

9 Lomax, Alan. 1968. Folk Song Style and Culture.

Washington DC: American Association for the

Advancement 10 Monk, William H., ed. 1861. Hymns Ancient and Modern for Use in the Services of the Church. London: Novello. Oxford English Dictionary. 1986. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 11 Pike, Kenneth. 1967. Language in Relation to a Unified Theory of the Structure of Human Behavior, 2nd edition. The Hague: Mouton. Routley, Eric. 1958. The English Carol. London: Herbert Jenkins. 12 Russell, Ian, ed. 2011. The Sheffield Book of Village Carols (new edn). Sheffield: Village Carols. Russell, Ian. 2012. The Derbyshire Book of Village Carols. Sheffield: Village Carols. 13 Russell, Ian. 2017. “The Performance Roles and Dynamics of a Christmas Carolling Tradition in the English Pennines.” In The Instrumentation and Instrumentalization of Sound: Local Multipart Practices in Europe, European Voices III, edited by Ardian Ahmedaja, 65–85. Vienna: Böhlau. 14 Salvation Army. 1963. Christmas Praise: The Carol Book of the Salvation Army. London: Salvationist Publishing. Sankey, Ira D., ed. c. 1890. Sacred Songs and Solos. London: Morgan and Scott. 15 Stone, Ruth M. 2008. Theory for Ethnomusicology. Upper Saddle River: Pearson-Prentice Hall. 16 Temperley, Nicholas. 1979. The Music of the English Parish Church, Vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

17 Turino, Thomas. 2008. Music as Social Life: The

Politics of Participation. Chicago and London:

University 18 Watson, John R. 1997. The English Hymn: A Critical and Historical Study. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Notes

2 See Russell

(2011) where there are 8 settings of

the carol; and Russell (2012) where

there are a further 13 settings.

3 ‘Liverpool’ is

attributed to Edward Harwood

(1707–1787) of Liverpool. It has

also been attributed erroneously to

John Hall (d. 1794). See Russell

(2011, 87–89).

4 Brady and Tate

(1700, 58–59) in

https://archive.org/details/newversionofps1733brad,

last access 4 May 2018.

5 See Temperley

(1979, 121 and 123, and 208);

Routley (1958, 120–23).

6 A snapshot

from 1823 lists 89 Christmas carols

in circulation that date from the

previous century. See Hone (1823,

97–99).

7 The origin of

this saying is attributed to

Benjamin Pollock, see Spitalfields.

http://spitalfieldslife.com/2009/12/17/penny-plain-tuppence-coloured/,

last access 5 May 2018

8 “Lining out”

or “precenting the line” was

prescribed by the Westminster

Assembly of Divines in 1644 to

combat illiteracy and encourage

singing in the reformed Protestant

Church in England. The practice was

also adopted in Scotland and in the

USA among the Old Regular Baptists.

See Temperley (1979, 82 and 87 and

89).

9 A contemporary

example of heterophonic psalmody is

practised in the Isle of Lewis in

Scotland. See, for example,

‘Stroudwater,’ which the

congregation sings in their native

Gaelic language.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=txIx9b07RhY

(accessed 5 May 2018).

10 Watson (1997;

see chapter 14, “The Oxford

Movement, and the Revival of Ancient

Hymnody”) and Gammon (1981).

11 Keyte and

Parrott (1992, 143–44) write at

length about the history of

‘Winchester Old’ but provide no

evidence

for it being used for ‘While Shepherds Watched’ before 1861.

12 The tune in

its original form was published in

Foster (c. 1817, II, 25–33) as

‘Psalm 47.

13 The tune

Lloyd was written by Cuthbert Howard

of Manchester (1856–1927) and was

published in its original form

in The Methodist Hymn-Book (1933) as Additional Tunes, no. 29.

15 See Sankey

[no date, c. 1890]

16 ‘Sweet

Chiming Bells’ was introduced to the

Sheffield area in the 1950s. The

composer is unknown. It is well

known in the Salvation Army – see

Salvation Army 1963, no 37 where it

is sung to ‘The bells ring out at

Christmas time.’ The transcription

in Russell (2011, 182–183), is based

on the playing of John Dawson

(1916–1999), a carol

pianist at pubs in Worrall and Oughtibridge.

17 A term coined

by Edward Hall, cited in Turino

(2008, 41).

18 See Russell

(2011, 58 and 84 and 121 and 133 and

166 and 171).

19 During

1997–2017 at Whitby Folk Week, an

annual festival held in North

Yorkshire, I have led twelve

workshops devoted to settings of

‘While Shepherds Watched.’

20 The recording

is taken from Glen Rock Carolers

1997, Voices of Christmas, CD, Glen

Rock PA, 24 December 1997, track 4,

by permission; see Russell (2012,

180–85), for transcriptions of ‘Once

More'.

|

Reproduced from The European Jurnal of Musicology at

How to cite this paper: go to https://bop.unibe.ch/EJM/article/view/8341

Esta obra está bajo una Licencia

Creative Commons Atribución 4.0

Internacional.

|